Canada is facing a serious health human resource (HHR) shortage of medical laboratory professionals, specifically medical laboratory technologists (MLTs).

In 2010, the Canadian Institute for Health Information identified that approximately half of all MLTs would be eligible to retire within 10 years , with the greatest impact felt in Canada’s rural and remote communities. This period of time has closed in on the professional community across all provinces and territories, resulting in a dramatic impact on organizations and employees.

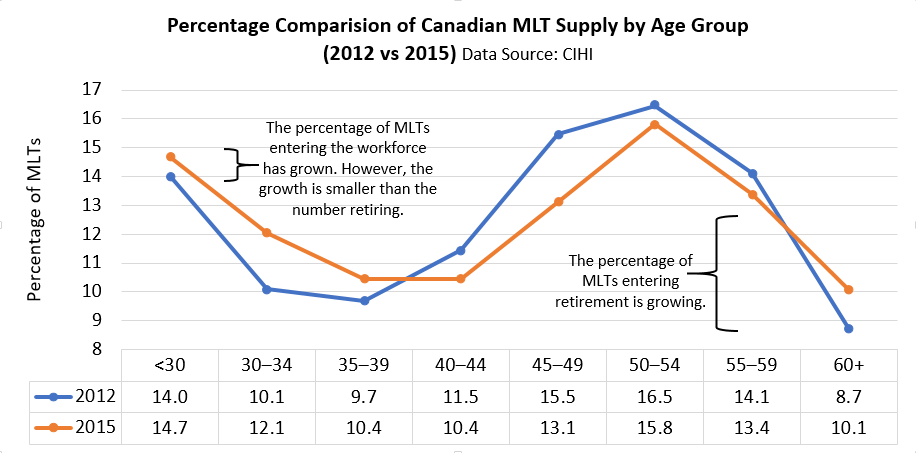

Recently released data shows that the greatest loss within the MLT workforce (2010–2014) was associated with those who are 21 to 30 years’ post-graduation. Unfortunately, there was not a corresponding increase in the number of MLTs obtaining certification in any age category. Notable results from Canadian Institute of Health Information data include:

- In 2015, approximately 40% of MLTs were 50 years of age or older. Ontario, Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia had the highest average age for MLTs;1

- MLTs had the lowest collective average age in 2015 (44.3 years old) since 2008, representing the shift in the profession’s demographics (see graph below).

Medical laboratory stakeholders have informed CSMLS that there is a large supply of individuals requesting admission to medical laboratory science programs across Canada. In fact, many academic programs report using wait lists for student entry. Thus, the bottleneck to certification and entry into the workforce is located elsewhere in the system pathway.

In addition to staffing shortages, workload measures and workload complexity continues to show an upward trend in the profession.2 For example, Ontario had projected a 1.8% per year increase for lab tests between 2005 and 2010; however, an actual increase of almost 4% per year was experienced resulting in the number of tests going up faster than workforce capacity.3

Keeping up with the latest advances and changes in testing, precision medicine, point-of-care testing (POCT) devices and diagnostic technology is not a small task. This means that students, professionals and academic programs must continually acquire large quantities of new knowledge to effectively deal with more complex equipment and situations; however, budget cuts, workload burdens and staffing shortages are to blame for the lack of clinical placement opportunities for students.

This scenario acts as a bottleneck in the student-to-workforce pathway, hampering HHR shortage solutions. Academic programs are required to procure a clinical placement site and spot for each student prior to entrance in the academic program. Issues surrounding such contracts limit the number of students that can enter the workforce at any given time and, ultimately, can contribute to an expanding HHR shortage. In order to the change this scenario, new models of education and clinical placement training are required. The Canadian Society for Medical Laboratory Science (CSMLS) acknowledges the importance of innovative learning environments and hands-on practice through clinical placement experiences to ensure the next generation’s expertise in medical laboratory science. Medical laboratory stakeholders are striving to increase simulation-based curricula to support evidence-based education models that decrease clinical time and increase the throughput of students into the workforce.

1 This data calculation does not reflect the CIHI methodology used to calculate retirement eligibility in the past. As well, the current calculation excludes data from British Columbia (large number of MLTs), Prince Edward Island and the northern territories (likely higher than average national MLT age as rural and remote). When considering retirement eligibility, reference to the CIHI 2010 information is most appropriate; however, the 2015 data provides current reference that the retirement eligibility remains in the absence of updated CIHI calculations.

2Assessment Strategies (2001). An Environmental Scan of the Human Resource Issues Affecting Medical Laboratory Technologists and Medical Radiation Technologists. Last retrieved April 11 2016 from http://tools.hhr-rhs.ca/index.php?option=com_mtree&task=att_download&link_id=5012&cf_id=68&lang=en Government of Newfoundland and Labrador (2011). Medical Laboratory Technologists Workforce Model Report Newfoundland and Labrador. Last retrieved April 11 2016 from www.health.gov.nl.ca/health/publications/MLT%20Workforce%20Model%20Report%20FINAL.pdf

3Sweetman A (2015). LABCON lunch plenary (Canadian Society for Medical Laboratory Science, CSMLS, Montreal), “Exploring the predicted increase in lab testing and the impending shortage of lab professionals.”

CSMLS has embarked on a long-term initiative to support academic programs, health care organizations and the future medical laboratory workforce in understanding current system gaps. Together, we want to increase the number of MLT students and entry to practice as well as collaborate to create evidence-based results that decrease the identified gap.

In a three-tiered project, information has been sought through formal surveys, an environmental scan, national forum discussions, targeted information gathering sessions and the Simulation Research Network.

Participants include three main stakeholder groups (academics, employers and students), but the pool expands beyond to other decision makers, such as regulators, topic experts and policy representatives. Project phases and associated reports can be found in the following table:

For the medical laboratory profession, as derived by participants at the National Simulation and Clinical Placement Educator Forum (2016), simulation is defined as:

“Simulation is an educational technique used to imitate real life scenarios (in part or whole), which enables participants to demonstrate and receive feedback on knowledge, skills, abilities and/or judgment. This can include but is not limited to communication, problem-solving, critical thinking and the ability to collaborate and work effectively within a health care team. Simulation can reflect simple to complex situations or processes and can be accomplished in any of the following examples:

- through interactive written case-based scenarios;

- computerized laboratory information system gaming;

- inter- or intra-professional role playing;

- standardized patients;

- task trainers such as rubber arms for phlebotomy;

- virtual simulation for specimen identification;

- haptic simulation;

- high fidelity simulation, or

- hybrids of any of these examples.

Similar to healthcare simulation, academic student simulation encompasses a range of activities with a broad common purpose of improving the effectiveness and efficiency of services and ultimately, enhancing competency acquisition by students in a safe and secure environment that reduces potential harm to patients, students, and the laboratory and general healthcare systems.” 4

4 Definition created during Phase 1b of CSMLS Project as derived by stakeholders: CSMLS (2016). Simulation and Clinical Placement National Forum. Last retrieved March 1 2017 from http://www.csmls.org/csmls/media/documents/resources/SimulationandClinicalPlacementNationalForum.pdf

CSMLS is spearheading a national initiative to gather evidence-based information, spur informed discussions and strategize practical solutions, which will, ultimately, decrease the impact of health human resource (HHR) shortages and profession-based workload burden.

The Simulation and Clinical Placement Initiative has generated a vast amount of data and support for greater inclusion of simulation in our academic programs as well as to support new clinical placement models to increase student seat capacity.

The high-level conclusions to date are:

Academic Program Environmental Scan (2016):

The use of a clinical placement may be enough to meet accreditation and program requirements, but there was a discussion to suggest that the limited quantity and potential impact of the current HHR shortage and fiscal constraints on quality may be negatively affecting certain organizations. It was noted that programs are doing their due diligence to meet demand, but the suggestion to create new education models is appropriate and recommended to support increase student throughput.Overall, simulation is supported as an incorporated component of medical laboratory science programs; however, a lack of standardization in its definition and use nationally is hindering this (see constructed definition here) Simulation Definition. This environmental scan demonstrates the growing trend for simulation to enhance curricula as well as the need for a national consensus on the direction it should take in the future. Programs were eager to understand more about simulation and obtain opportunities to grow a simulation network; however, budgetary constraints and lack of information exchange are hampering further simulation incorporation into curricula. Evidence-based research focused within the profession would support each of these goals and provide the basis for business cases to evolve education models, as determined by the needs of students and programs within the current health care and educational constraints.

Recent Graduate Clinical Placement Experience Survey (2016):

A survey was disseminated to individuals who had successfully passed the CSMLS certification exam within five years of the survey date (response N=483). General satisfaction for clinical placement preparedness and on-site training was high, meeting student demands in regards to their technical and practical skills and ability to practice skills on quality equipment. Graduates expressed less satisfaction in areas of safety and noted concerns about specific experiences, indicating an area for further review. More specifically, the data reflected how HHR shortages impacted medical laboratory professionals, which in turn impacted the student experience. Comments centred on increased stress and burnout associated with the change in staffing and workload models and added complexity of monitoring students during constrained times. These factors have started to come to the surface and are likely impacting students, with projections for this to increase given the evolution of the health care system.

CSMLS Simulation and Clinical Placement Educator Forum (2016):

The Simulation and Clinical Placement Forum can be considered a great success, having achieved the goals set for the day. Attendees were able to come to a consistent national understanding of the positive impact simulation can have on enhancing curricula through quality improvement and decreasing clinical placement hours. The following are key conclusions and recommendations from the day’s event:

- Simulation can now be understood as an evidence-based technique that is capable of reducing clinical hours in a positive and meaningful way for students;

- A new model to increase communication between programs and cultivate simulation curricula sharing is required to support program change moving forward;

- Programs are engaged and invested in looking towards future changes in curricula to support students to achieve competency through the highest quality clinical placement and simulation experience possible;

- The profession-specific simulation definition, derived by Forum participants, and information contained in this report can be used to support a national understanding of simulation and be communicated to administration for business case models.

In order to continue the simulation and clinical placement movement, there are specific recommendations to maintain momentum and support programs in achieving change. These initiatives include, but are not limited to:

- Create a discussion platform for simulation and clinical placement evidence and knowledge sharing (e.g., information repository, conference and teleconference);

- The employers of clinical sites should be brought into the conversation in the next project phase as a major change in programs will be dependent on their participation;

- Through further information gathering from other professionals and profession-specific research, determine how standardized simulation for programs can be created.

Simulation Knowledge Exchange – Research Network (SimKERN, 2017)

SimKERN was brought together by CSMLS to create networking and knowledge transfer opportunities for medical laboratory science programs across Canada to create simulation and clinical placement research that supports the quality of student learning and experience, increases the quality of program curricula through evidence-based information and supports employers to increase student placement capacity. It is a direct result of the recommendations made at the Educator Forum in April 2016.

Overall, a goal was set to increase the national recognition of medical laboratory science programs as innovators of student-centred curricula and become leaders in simulation research. This group was constructed from the recommendations that were made by the educators and stakeholders at the Educator Forum in April 2016.

The group committed to creating quality assurance and research projects during 2017, support the Simulation and Clinical Placement National Discussion – Teleconference Series and contribute to a large-scale research project.

Simulation and Clinical Placement National Discussion – Teleconference Series (SimTele, 2017):

SimTele was created by CSMLS and SimKERN, consisting of individuals who share a common interest in creating profession-specific research and evidence-based information on simulation and clinical placement topics. Together, the group increased the national understanding of medical laboratory science through research and knowledge transfer activities within a monthly teleconference structure.

Employer Survey (2017):

A two-part survey was created to foster information from employers on their clinical setting needs associated with students during their practicum as well as an understanding of simulation as a useful tool to support student learning. Key conclusions can be derived from the results. As a highlight, some of the conclusions informed a large-scale research application, including:

- Areas where employers identified that specific disciplines and topics did not need to be taught in the clinical setting;

- Identification that 21% of clinical sites surveyed said they could take on more students;

- Reasons why clinical sites could not take on more students focused on burnout, workload and lack of staff to supervise students;

- Recognition that 74% of employers said students were sufficiently prepared for clinical placements (indicating room for improvement);

- Disconnects between educator, student and employer perceptions on quality of different teaching components during clinical (e.g., safety, soft/essential skills);

- Majority agreement that simulation is an effective technique to educate medical laboratory students.

Employer Forum (2017):

In alignment with the Educator Forum conclusions, CSMLS completed the project Phase 2b, an Employer’s Forum (April 29, 2017, in Toronto, ON; cohosted with The Michener Institute of Education at UHN) that brought together private and public health care organizations and representatives, who support student learning in clinical environments to continue the educator’s conversation. For purposes of this discussion and the related Forum, ‘employers’ are defined as managers, supervisors, clinical instructors/preceptors, organization representatives and medical laboratory professionals who work directly or indirectly with students. The Forum was able to bring together information sharing on the perspectives of key stakeholders as well create dialogue and brainstorming activities for solutions to barriers in the clinical placement bottleneck. Results of direct importance to the proposed research include the general consensus that the creation of simulation-based research and evidence-based curricula are imperative in moving forward, continued networking between academic programs and clinical sites should be of high importance when creating any research for clinical sites and a general sense that clinical sites are primed to take actions to make positive change happen. It can be concluded that the proposed study is in line with the expectations discussed at the Forum and CSMLS continues to answer the call of its medical laboratory stakeholders.

CSMLS Position Statement (2018):

CSMLS supports the use of simulation in the academic environment as an educational technique to assist students in achieving CSMLS-defined competence. The Position Statement acknowledges the use of simulation to partially replace and/or enhance clinical placement training as a viable and contributing solution to increasing the medical laboratory workforce in Canada.

Call to Action (2018):

CSMLS is in the process of disseminating a Call to Action for academic programs, clinical placement sites, laboratories and the profession to address the national HHR shortage of medical laboratory technologists within Canada.

For more information, please read the Call to Action (coming Fall 2018) or contact research@csmls.org.

This website provides a Letter of Commitment template to showcase laboratories and health care organizations interested in creating or reinvigorating opportunities for clinical placement training of medical laboratory technologist (MLT) students. The Letter advocates for dedication and investment to ensure such organizations work with key decision makers to increase clinical placement sites/student spots while maintaining a high standard of training.

For organizations planning program reviews or initiating improvement strategies, senior managers and leaders might not be aware of the health human resource (HHR) shortage of medical laboratory technologists in Canada, the importance of the CSMLS initiative to increase academic seats and clinical placement spots across Canada or the collaborative model taken to identify and validate supporting evidence. It is important to raise awareness and gain the support of such influential health care leaders so that change initiatives can be actioned.

The messages contained within the Letter can be used as the platform for initial dialogue with key managers and leaders responsible for decision making on matters of training, safety/quality improvement and human resource allocation. The initial communication may take the form of a meeting, where the content of the letter is used as the basis for discussion. This can then be followed up by a memo, letter or email as appropriate for the local context.

The Letter is a sample of what your organizations can support through signing and submitting to CSMLS; therefore, where appropriate, local information can be inserted or the text modified to reflect local style. Please forward an electronic copy of this Letter, with signatures and official letterhead, to Sierra Paprocki, Executive Assistant to the CEO -

SierraP@csmls.org. This letter may be displayed on the CSMLS website or used in other communications with stakeholders.